Wearables Challenge the Display Industry to a New Round of Development

Wearables Challenge the Display Industry to a New Round of Development

Activity trackers, smart watches, and near-to-eye displays represent three major areas of wearable technology. In order to maximize on the potential of any of them, developers must combine forward thinking with enough humility to learn from the past.

by Paul Gray

IN 1916, the British Army faced a dilemma: trench warfare with its creeping barrages made accurate timekeeping in the field a necessity. The words “synchronize your watches” were used for the first time. Pocket watches were unsuitable for trench warfare, so wristwatches, until that time a piece of jewelry worn by ladies, were issued to all officers. As men returned home on leave wearing wristwatches, the devices became viewed not as effeminate but as the very mark of masculinity.

Nearly 100 years later, display and consumer- electronics manufacturers alike are hoping that new types of wearable devices will find that ideal spot where they simultaneously fulfill a need and exist as an object of desire. The consumer-electronics industry is facing bleak days: the flat-panel TV business has peaked; iPad shipments are declining; and, while smartphone volumes are still growing, the best days of profitability – at least in terms of the products we know now – look to be over. What is surprising is that the pipeline of up-and-coming consumer-electronics devices is so empty. What makes it worse is that the smartphone is cannibalizing its way through pre-existing categories such as cameras and navigation (and even wristwatches). The emergence of wearable devices in 2013 and 2014 has, therefore, been seized by an industry hungry for a high-growth product that will provide a high-volume, high-value business for the future. At present, there are roughly three classes of such devices: activity trackers, smart watches, and near-to-eye displays.

Activity Tracking

Activity trackers are small devices that are usually worn on the wrist, although formats such as belt clips and foot pods are also common. They are essentially data-loggers, using accelerometers to measure movement. Algorithms then interpret the data set as running, walking, etc. This enables the wearer’s activity level and calorie consumption to be estimated, along with duration of aerobic activity. At the most basic level, a tilt switch and counter can log steps, although more refined versions use barometers to differentiate between climbing stairs and walking on flat surfaces. Adding more sensors improves accuracy, although the data remains an estimate, and some activities are hard to measure: the difference between walking and cycling being one. Such devices generally have simple displays: a paired smartphone, tablet, or computer typically does the heavy lifting in terms of display.

These are behavior-modification devices, and their true power (once the novelty wears off) is in the motivational effect of their apps. Well-written apps are addictive and motivating; poorly created versions give the impression of being bossy and rude.

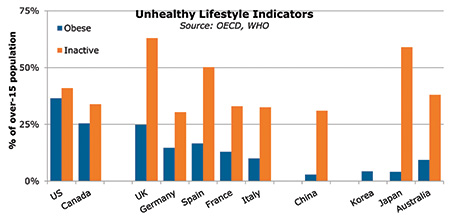

The potential of such devices as behavior-modification tools is huge, considering the costs to healthcare systems from obesity and inactivity (Fig. 1). The UK health ministry estimates the cost of a heart attack as £50,000 (around $80,000) per person in healthcare alone. Even if only 1% of people in the World Health Organization chart in Fig. 1 changed their lifestyles, the benefits could cover the outlay in seeding everyone with fitness trackers. Such thinking appears to be taking hold in some corporate wellness programs, and companies in behavior-modification businesses such as dieting and weight loss are likely to adopt these kinds of trackers.

Fig. 1: Obesity and inactivity represent huge potential costs to healthcare systems. Countries where these conditions are prevalent represent potential markets for fitness tracking devices.

Smart Watches

Smart watches are the most obvious wearable product in that they add computing functions to an existing product category. They are inherently different from other wearables in that they are essentially communication devices. Their predecessors, smartphones, have evolved from phones to media-consumption devices and are in essence pocket-computing Swiss army knives. In recent years, their format and especially their screen size have sacrificed portability for improved media consumption. In addition, Apple has educated consumers to appreciate (and demand) a display as good as high-quality magazine printing. Competition did the rest. The phablet category introduced an even larger device that was good for everything but holding to the ear as a phone or using while walking.

DisplaySearch research suggests that around 25% of women in Asia have hands too small to hold larger smartphones. Against this background, the smart watch makes some sense. With phones optimized for longer tasks (such as a 5-minute video clip or an email), a gap has emerged in the market for a device targeted at very brief

tasks and information. Such tasks include simple, timely information of very high value in a simple format. Imagine being in a rush-hour crowd at a busy railway station: knowing when and where to catch the connecting train would be priceless. Removing a phone from a pocket, entering the code, and then starting the right app in order to obtain this information would be time consuming and difficult in a crowd. A well-designed smart watch could be the answer. From this basic value proposition, manufacturers have used their imagination to add features accordingly: fitness tracking capabilities are popular in smart watches. The final dilemma facing makers is whether to nod to the tradition of watchmaking or fly against it: should smart watches look like watches or take on a completely new aesthetic? Motorola’s Moto 360 looks like a watch; Samsung’s products are more like smartphones on the wrist, while Apple has ventured somewhere down the middle, with watch-like detailing but a rectangular screen.

Near-to-Eye Displays

Near-to-eye displays are the most futuristic and require the healthiest dose of optimism on the part of developers and users. There are two main types: Google-Glass-type glasses with a head-up auxiliary display providing contextual information and fully immersive virtual-reality headsets intended to present a completely new world that fills the senses. Google did a superb job of publicity with Google Glass, which definitely captured the popular imagination. However, stories about its use reveal a deep truth that societies are not quite ready for such devices.

To begin with, it is illegal to wear Google Glass while driving in most countries. The fact that one man wearing a pair (switched off, just for the corrective lenses) in a cinema led to several hours of interviews with the Department of Homeland Security reveals how much things would have to change in order for these

devices to be universally accepted.

Furthermore, national privacy norms differ significantly. Europeans are generally more sensitive than Americans about privacy; wearing Google Glass in a public space in Germany (for example) is likely to meet with a cold reception. Consumers in Germany are very sensitive to being recorded by others, with or without their knowledge. Recent European legislation on the right to anonymity on Google is a case in point, while Google Streetview in Germany has many buildings blurred out at the request of their owners. However, societies that accept such functionality could react positively. The meteorite air burst in Chelyabinsk in 2013 was widely captured on video, largely by dashboard cameras. Such cameras are popular in Russia, as motor insurance fraud is a severe problem.

Necessity is the mother of adoption. As a result, we expect that near-to-eye glasses will be deployed in private premises where they improve productivity or where touching screens or keypads is problematic; sterile environments such as surgery or food processing, as well as production lines, servicing, and warehousing, would seem to be promising candidates. In such applications, the glasses would need to be integrated with the enterprise’s data systems and would likely be part of them.

For example, digital signage turned out to be not so much about the display technology as about systems to manage the information – so professional wearables will more be about managing the information presented to the wearer. For an airline customer-service application, the biggest challenge is how to get correct relevant information immediately to the customer services agent: (“Good morning, Mr. Gray, your flight will now depart from Gate 24”).

Virtual-reality headsets have been around for a long time; developers seem to assume we all want them more than we actually do – similar to paperless offices. Sega teased with its VR headset from 1991 to 1994, but never released it. There are two main issues that need to be overcome. First, a safe-use area is necessary if people are to wear them without inadvertently falling down stairs or hurting themselves. The second is the challenge of presenting a real experience. The failure of 3-D was caused in part by the brain picking up contradictory sensory cues that caused eyestrain and broke the sense of immersion. In the case of VR headsets, the disparity between balance sensing and vision will cause motion sickness for some and reduce the effect for many more. Furthermore, the fact that Oculus Rift prototypes used a stripped-down Samsung smartphone and Google’s cardboard smartphone mount suggests that the category is wide open to cannibalization, at least in the high-volume consumer segment.

In considering this market, it is vital not to forget people! The moment something is worn it becomes a part of personal identity. People want to look individual and different. They identify so strongly with smartphones that they customize them with cases unlike the matte gray Nokias of the 1990s. The wearables market is inherently different from consumer electronics in that product diversity is good. Therefore, it is likely to have far more niches in design, construction, and materials: “One size fits all” will not work. Amazon.com currently has over 300,000 watch models for sale; Casio has over 1500 live watch products. Prices range from $10 to over $100,000, and the device design transcends function. For smart watches, displays are part of this differentiation, from the watch-like round face of Moto 360 and G-Watch R to the rectangular screen of Samsung’s Gear S.

With design being a greater factor than for other consumer-electronics types, we expect that competition will play out a little differently. It appears unlikely that a single company can dominate in the “winner takes all” dynamic of phones. Instead, this is more likely in operating systems because smart watches are essentially software devices. So the balance is likely to favor more hardware variety but based on standard platforms. Apple’s challenge will be to satisfy its consumers’ desire for individuality.

Different Scenarios for Success

Unsurprisingly for such a new product type, display technology is not yet mature and no technology is clearly superior. While consumers have been educated to want a bright, sharp, high-contrast display, the biggest constraint on designers is trading off bulk and battery size. Features of questionable value in applications such as TV have real benefit in wearables: curved screens enable products to fit more closely and naturally while bendable displays promise to be more comfortable and robust. Depending on the designer’s intention, almost every technology has its place. For a long-lasting light device, then e-Paper or bistable LCDs are optimal; for a colorful display on a smart watch with a bold high-tech statement, AMOLED displays would be more appropriate. Interestingly, some technologies that have been recently out of favor, such as e-Paper and passive-matrix OLED technology, can expect a re-appraisal as they create new opportunities: e-Paper enables a breakthrough to the power problem, enabling a light, thin watch, while PMOLED technology provides a low-cost punchy curved or flexible display for simpler devices.

The biggest challenge for designers and product managers is deciding what part of the market to address and how to tailor an optimal product. The usual consumer-electronics industry habit of adding features will be severely punished by poor usability and short battery life. Consumers are a poor guide: many consumers we interviewed wanted video capability – yet a 1-in. screen would be almost unwatchable and most of us would pick the phone from our pockets instead to watch video. Savvy product managers will decide on a few functions to do well, be it a device optimized for specific sports by its motion-capture algorithms and form (e.g., waterproof for swimming, impact resistant for squash) or for an ultra-thin and stylish band with an OLED display and jewelry standard of finish.

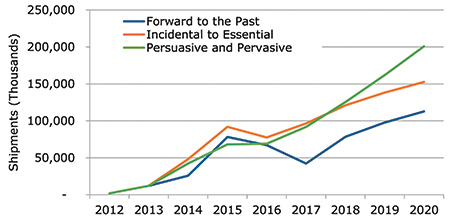

DisplaySearch has constructed several scenarios in which to explore market development. In all scenarios we have modeled some elements of hype. Wearables are in part fashion items and some consumers will purchase them simply to have the latest thing. Our three scenarios appear in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2: DisplaySearch has created three potential scenarios for the wearables market through 2020. All show growth, but the “Persuasive and Pervasive” model shows the steadiest and highest long-term growth.

In the “Forward to the Past” scenario, a strong fashion surge will be followed by cannibalization from smartphones, which remain dominant. Fitness bands prove transient as consumers use tracking apps in their phones or add small transponders for exercise. “Incidental to Essential” has a fashion element, but growth is underpinned by strong platforms that command consumer loyalty, such as Android Wear and iOS. This scenario also assumes that fitness devices establish a lasting place in the market. For “Persuasive and Pervasive,” the initial hype is very limited, as consumers struggle to understand why they need wearables. Adoption is driven instead by healthcare providers, sustaining long-term growth. However, the market adopts a more business-to-business nature.

Underpinning the scenarios is the knowledge that fashion is a double-edged sword: the bigger the surge, the greater the risk of a crash afterwards. A huge hype for smart watches with poorly thought-out value propositions runs the risk of consumers confining the devices to a drawer after a few months’ frustration. If that happens, the smart watch will be a repeat of the digital photo frame or 3-D debacles, where over-promoted products of little lasting value hit the market and then fizzled.

In my personal experience of wearables this year, I have found some surprising things. Of three fitness trackers, two have been lost relatively quickly when their straps popped open. One was a direct result of its addictive app – I decided to see what it would make of kayaking as exercise; the other disappeared somewhere between the jet bridge and baggage reclaim in an airport. However, my trusty Casio LCD chrono watch has survived 20 years of sailboat racing and salt water. Wearables makers need to have the humility to learn from a century’s experience in making wristwatches and adopt a few of those tricks in building

the category. The potential health benefits are huge, and the need is there. Imagination will be the key to the next step – and display technology has its part to play as the very face of the product. •

Paul Gray is a principal analyst with DisplaySearch (part of IHS). He can be reached at Paul.Gray@displaysearch.com.